Your World Is Your Street: A Studio Visit with Agosto Machado

Studio Visit

Agosto Machado. Photograph by Scott Rossi.

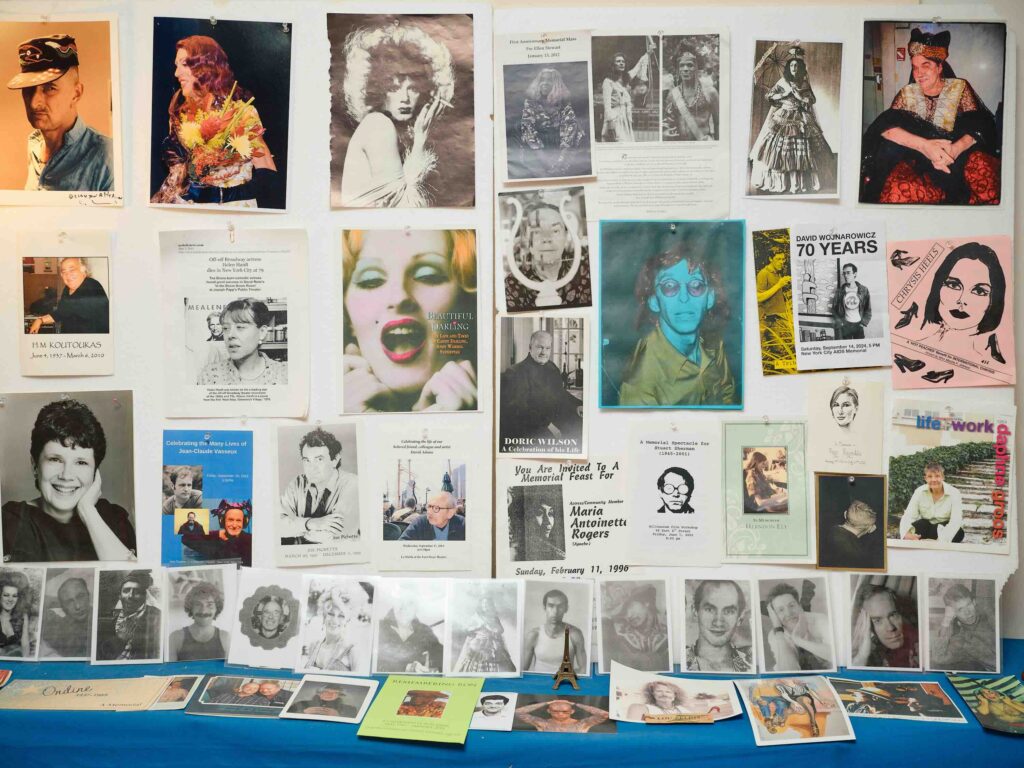

Agosto Machado’s apartment and studio on East Third Street is crammed, floor to ceiling, with steel bookcases bursting with books and boxes of files. Colorful printed fabrics are draped over the shelves, concealing most of their contents. In the areas left exposed, there are framed photographs of icons like the Warhol muse Candy Darling and the gay liberation activist Marsha P. Johnson, arranged around candles and trinkets as if to form small devotional altars. The space is small, but Machado welcomed me in on a late April day. He had laid out a bottle of Evian for me, and a packet of Pepperidge Farm butter cookies. He had rolled his bedroll into the bathtub to make space for us to talk. I gestured at the fabrics hanging over the shelves to ask if they’re for privacy. “Oh no,” he said. “It’s aesthetic. Like makeup.”

A Chinese Spanish Filipino American orphan raised on the streets of Hell’s Kitchen, he befriended and eventually influenced multiple generations of downtown artists, among them Jack Smith, Peter Hujar, and Ethyl Eichelberger. Machado, who doesn’t share his age (“A lady never tells,” he said), has been a witness to decades of cultural moments in New York: the experimental theater of the early sixties, Warhol’s factory, the Stonewall riot, the AIDSepidemic, the gentrification of downtown Manhattan. He is eager to be of use as an oral historian—to evoke, as his art does, the lives of the artists he has known, many of whom were lost to AIDS. He has always collected the world around him, accumulating protest pins and street flyers, photographs, funeral notices, bits of gems and glitter, a pair of Candy Darling’s shoes. In recent years, Machado has begun delving through his archives to create shrines and altars, like the ones that appear in his portfolio in The Paris Review’s recent Spring issue.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve been described as a performance artist, a “Zelig-like icon,” a muse, an activist, and an archivist. It’s difficult to define you, but you define yourself most often as a “pre-Stonewall street queen.” What does that mean to you?

AGOSTO MACHADO

It came out of the happenstance of not having a regular place to live when I was young. For street queens, your world is your street. Where do you get information? In person, on the street. People would say to each other, Did you hear that place was raided? Do you know who just died? Do you know who’s in the hospital? Do you know who got picked up in Bellevue? And so forth. I was nobody and I had no place to live. I was dependent on the kindness of strangers. That’s a quote from Tennessee Williams. And there were people who, even if all they had was a bag of potato chips, they would share it.

INTERVIEWER

For The Paris Review, you titled your portfolio Downtown (Altar). Can you tell me about the two pieces by Gilda Pervin? One is a pin, and the other is a rectangular sculpture. They’re made of colorful clay, with bits of wire and marbles and beads stuck into them. How did they come into your possession?

MACHADO

Gilda Pervin is ninety-one years old now. She came to New York when she was forty-six. She was married and she had children. She wanted to express herself. I had started working with Ethyl Eichelberger, who lived on Spring and Elizabeth. Where the Elizabeth Street Garden is now, there was a vacant lot where people threw garbage and what have you. But on a window ledge nearby, there was an accumulation of these objects. Someone had taken the time to put them there. That was Gilda Pervin. I said, “Whoever this artist is, I hope to eventually meet her.” And those are the pieces she gave me. For forty-five years, I have moved them around in different installations. And now, they’re part of an altar, which is really a shrine. It’s going to be in the museum as one piece.

INTERVIEWER

What prompted you to collect and archive the world around you? Did you always feel that you were living through history?

MACHADO

No. Emotionally, this is what I embraced because I had nothing. I thought, These memories dwell within my heart. These people, if they’d had time, would have done so much more. So I collected these mementos of the street queens. I collected photographs too. Cameras were a luxury, even an Instamatic. All around us, under this fabric, are boxes of snapshots. There are thousands hidden away, and I hope to eventually excavate them and do little zines dedicated to various people, to acknowledge their existence and their contributions and the bravery of them expressing themselves and doing their art. Once AIDShit, obviously, so much was lost. But as long as there’s oral history, there’s wonderment.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

INTERVIEWER

If you could resurrect one downtown venue that has since closed for one night, which one would it be?

MACHADO

The Silver Dollar. The Silver Dollar restaurant was on the corner of Washington and Christopher. During the day, it was filled with office workers from the post office and what have you. Little by little, in the afternoon, the drag queens came in, and then at night it was the street queens who went out to the men in the trucks and made money. The juxtaposition of the street queens, the homeless people, the people who wanted drugs—it was a clearinghouse. Working at the restaurant were these Greek immigrants, most of them from small villages in Greece. Now they lived in New York, and they were probably thinking, Thisis America? It’s not like in the movies! They were surrounded by all these people in women’s clothes. They’d yell, “Mary!”—that’s a generic name for us, Mary. If you didn’t know the girl’s name, you’d say, “Hey, Mary.” They’d yell, “Mary! Your hamburger’s ready!” and all the heads in the place would turn at once.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

INTERVIEWER

Your friendships have been central to your life and to your artistic practice. What would you say you’ve learned from them?

MACHADO

I learned about community. I did twelve years of caregiving during the time of AIDS, and that was an awakening. The downtown community turned their backs on us—this is before ACT UPand so forth. I would visit sick people and do what I could or take them to doctors. I was very discreet, because people didn’t want others to know that they were sick. Word spread that Agosto was helping “them.” I stopped going to gay bars because people would move away from me. They thought that if I was helping people with the disease, then I had the disease. I couldn’t believe that people would not help their neighbors.

INTERVIEWER

Things have changed significantly since then, in terms of how we think about gender and sexuality. What do you notice, as part of an older generation?

MACHADO

I’m in an artist collective called Pioneers Go East, and we performed several years ago in Hell’s Kitchen. And this young person who looked like they were a high school senior said, “We’d like to welcome you here. We’re going to go around the room, and everyone is going to announce their pronouns.” I said, “What is a pronoun?” And then they started—he/him, she/her, they/them. And then I remember I said, “She/him.” You’re always learning. We think we know a lot, but I learn something new every day, and it’s a blessing.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

INTERVIEWER

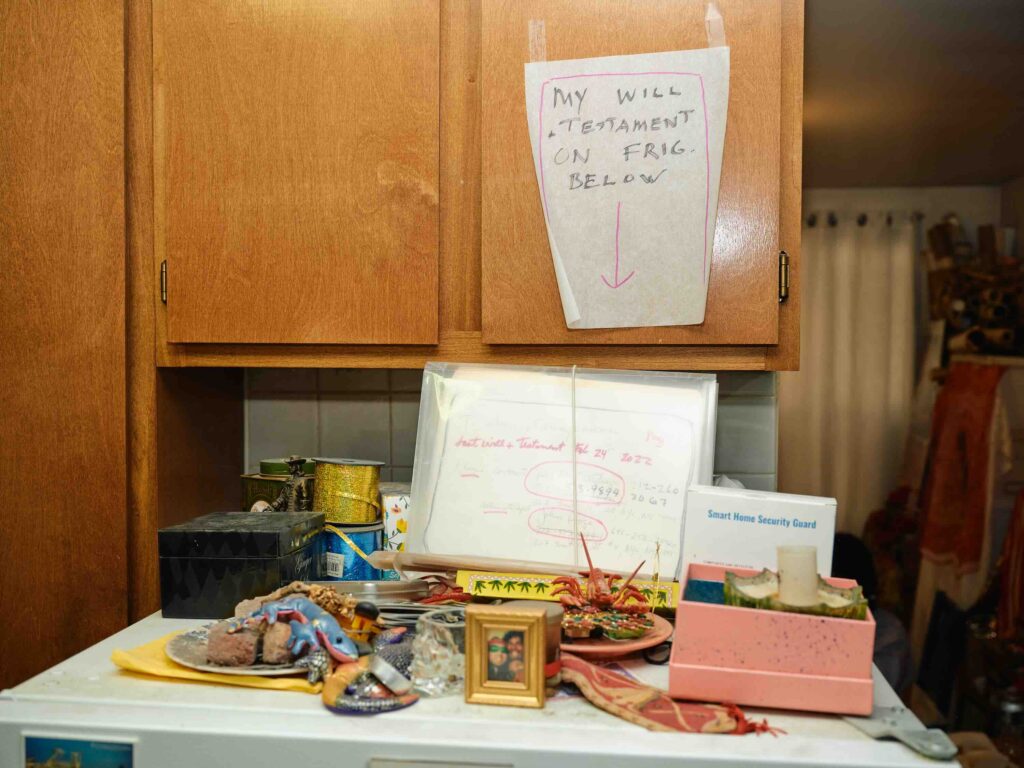

So much of your recent work has focused on memorializing people who have died. Have you given thought to how you would like your own life to be memorialized?

MACHADO

I do not want a memorial or a funeral. I want to be remembered as I was. I’m going to join all our friends. I believe in heaven and reincarnation. I prepaid for my cremation. Over here by the window are ten people’s ashes—Marsha P. Johnson, Holly Woodlawn, Jack Smith, and a number of friends who were at the Play-House of the Ridiculous. Just a little bit of each of the ashes of these very dear friends who have departed. I have already written my will, and it says that all these ashes will be mixed with mine into one receptacle and then they will all go into the Hudson River, not far from where Marsha’s body was found. It will happen discreetly and quietly.

INTERVIEWER

Are you afraid of death?

MACHADO

I do not have any gripes about passing. It is all part of life. I am far from perfect. I accept all my flaws and I know that I’m privileged to have lived this long, to be able to share some of the names of people who should be remembered. This is my tribute, as a street queen on Christopher Street. All these people … I’m going to start crying. All these people contributed to my life.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

Nadja Spiegelman is the author of the memoir I’m Supposed to Protect You From All This, as well as four children’s books, including Lo